By tracking shifts in communication over time, we gain insight into how people view the world and how those views change.

This is more complicated than simply tracking the raw frequency of words over time. You might see that the word ‘happy’ is becoming more popular over time, but this does not necessarily mean that it reflects more positive sentiment. It might be that the word ‘happy’ is replacing similar words like ‘joyful’; it might be that people are talking more about their emotions in general (both positive and negative); or it might reflect some other factor like the popularity of a band like ‘Happy Mondays’. One of the biggest mistakes that people make in language analysis is trying to draw insight from raw frequencies.

Both X and Y

We use a fairly sophisticated mix of linguistic technologies to generate actionable insights for Idibon’s customers. But there are some fairly easy techniques that anyone can use. A great example is from Tyler Schnoebelen’s recent post on coordination structures: ‘both X and Y’.

In English, we tend to put the most salient element first in ‘both X and Y’ constructions. There are still plenty of confounding factors. For example, we tend to put heavier words last (“both pride and prejudice“) and prefer temporal ordering (“both morning and afternoon“). But these confounds aside, our ordering of items generally reflects our perceived importance. The importance of ordering is broader than ‘both X and Y’ constructions and often leads to disputes (Hewlett and Packard famously settled their company name order by a coin-flip), but ‘both X and Y’ provides a nicely constrained context here that is easy to analyze.

We took all the ‘both X and Y’ constructions from the Google Books Ngram dataset, and measured how the preferred order has changed from 1800 to the present day. This gives us 80 Million uses of ‘both X and Y’ over 200 years, with many interesting patterns. We ranked the constructions by the greatest change over time, and looked at those that changed the most. Here’s what we found:

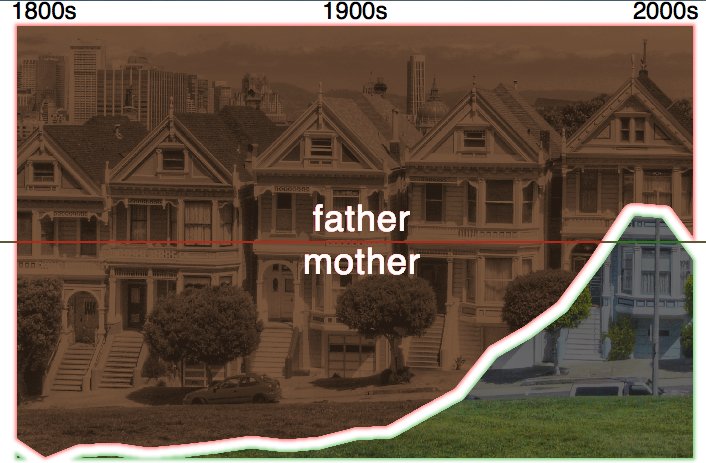

Mothers are now equal to fathers

During the 1800s we really only said ‘both father and mother’. Throughout the 1900s the mothers staged a comeback, and now we’re at the point of equality where ‘both father and mother’ and ‘both mother and father’ appear equally. This trend is also seen with ‘both maternal and paternal’, showing that the pattern is broader than simply the words themselves, and really is an indicator of social change.

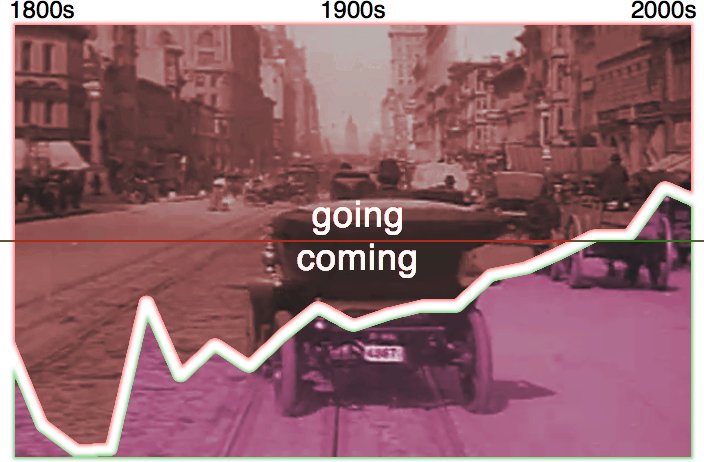

We are now coming more than going

We used to almost exclusively say ‘both going and coming’, which sounds odd to me, but now we can see that ‘both coming and going’ is more popular.

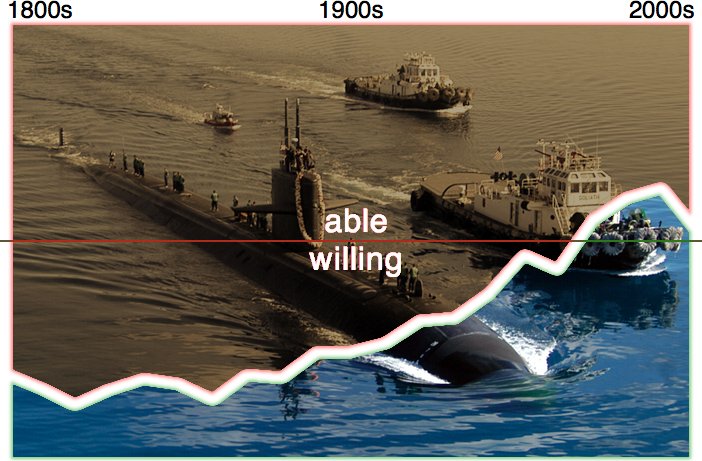

We are more willing but less able

Another construction that sounds odd, ‘both able and willing’ was once more popular than ‘both willing and able’. I was surprised to see that people actually use the ‘able and willing’ variation about 40% of the time—is this just my perception or do you use this?

The top 30

Here’s the top 30, ordered by how much they have changed over time (the current most popular order is what’s listed):

- morning and night

- willing and able

- mother and father

- heat and electricity

- marine and fresh

- coming and going

- near and far

- tea and coffee

- Lords and Commons

- maternal and paternal

- law and fact

- live and dead

- income and capital

- eggs and sperm

- young and old

- you and us

- waking and sleeping

- gray and white

- Irish and English

- individuals and nations

- minimum and maximum

- stocks and bonds

- you and he

- front and back

- here and there

- acidic and basic

- him and herself

- literary and scientific

- internally and externally

- left and right

You read that last one correctly: we used to say ‘both right and left’ more than ‘both left and right’.

One of the most striking aspects of this list is how clean it is. By choosing a coordinate structure like ‘both X and Y’, were are getting meaningful pairs of terms that we can track over time. Many of these trends hold up across different terms. For example, the increase in preference for ‘internally’ over ‘externally’ can also be seen in an increasing preference for ‘inside’ coming before ‘outside’.

To be completely certain about these trends, you would need a little more processing: removing duplicate documents, allowing for changes in the types of materials that are published over time, and adjusting for some more complicated linguistic phenomena like prosody. But for an experiment that anyone can reproduce, searching for ‘both X and Y’ constructions on Google Books Ngram dataset gives you a useful first step in identifying trends beyond simple word counts, and (hopefully) an appreciation for the importance of detailed analysis.

And remember when I said that there was bias to have heavy elements last and to maintain temporal ordering? It turns out that the biggest change violates both, with ‘both night and morning’ now becoming ‘both morning and night’. I leave it to you to consider why!

Robert Munro

@WWRob

p.s.—Our offices are in one of the photographs above.

Edit

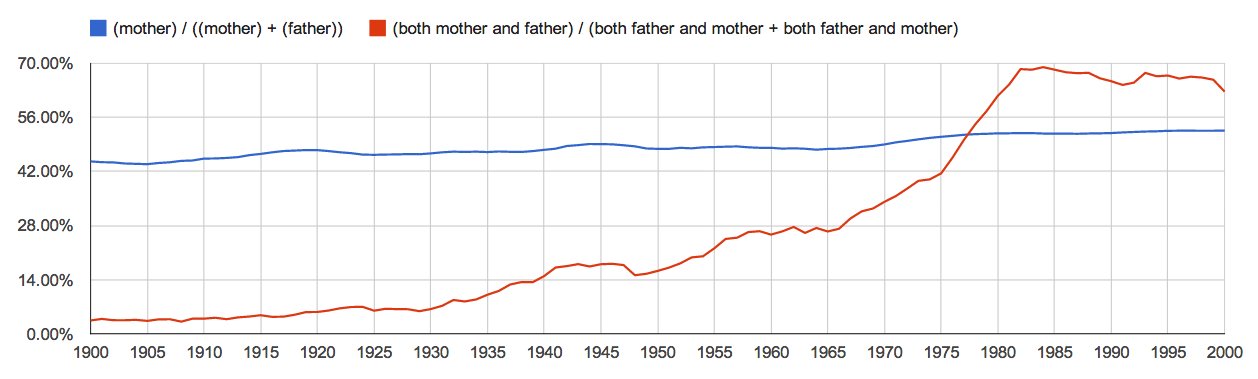

You can also try some of these directly in the Google N-GRAM corpus by expressing the words in equations (hat tip to Ben Zimmer who alerted me this possibility):

The Mother and father graph should look something like this:

It it a nice way of showing that while ‘mother’ has hovered around 50% of all mentions of ‘mother’ or ‘father’ for the last century, the ‘both mother and father’ ordering has dramatically increased.

Enjoy!!